Introduction to Impact Evaluation Methods

by Rhea Bisaria and Aditi Acharya

The Economics Society, in collaboration with the Centre for Economic Research, St. Stephen’s College hosted Academic Summit 2.0, a series of lectures on Applied Economics from 25th to 27th of March, 2019.

The society was privileged to host Dr. Bidisha Barooah who delivered a lecture on the topic ‘An Introduction to Impact Evaluation Methods’. Dr. Bidisha Barooah is Senior Evaluation Specialist at the International Initiative for Impact Evaluation (3ie) and is also a senior research assistant at the Delhi School Of Economics.

Dr. Barooah spoke about the unique field of impact evaluation, the different methods involved and contexts in which impact evaluation plays an important role, while illustrating the key principles required for good evaluations.

Rhea Bisaria (RB) and Aditi Acharya (AA) had the privilege of interviewing ma’am and are delighted to share the transcript of the same.

RB: In recent years, policies based on impact evaluation have been receiving a lot of focus in developing as well as developed countries. In this regard, what do you think of India’s attention to these policies, has it been adequate or is there a lack of attention in this field?

BB: I think the field is certainly changing and we are finding that Indian policy makers are becoming more open to evidence-based, informed decision making. There have been a number of cases where similar evaluations have gone on to become the foundation for informed large-scale policy making. However, compared to many other countries, we are lagging behind. I think the focus in India is very much still on an input- based evaluation rather than an outcome- based one. But we do see that in some pockets, particularly in some government departments, there has been a lot of buy-in for evidence based decisions.

AA: People have often been skeptical about the impact of the impact evaluation programs, considering how governments have continued with projects which have not been successful empirically. What do you think are the reasons for the same and how do we overcome it?

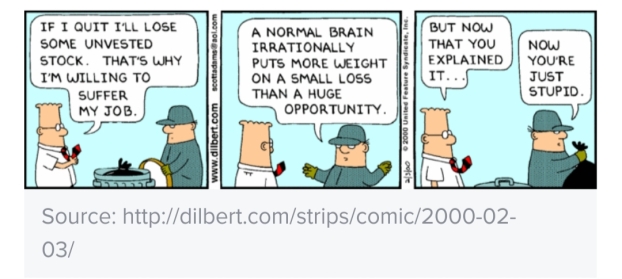

BB: Well, that’s something that even we at 3ie are grappling with, on how to increase accountability. We saw, in the lecture, that the constraints of a policymaker are very different from the constraints of an enumerator. A policymaker typically has to complete a task by a deadline and one of the feedbacks that we’ve constantly received, from our interactions with policymakers is that the evaluation results don’t reach them on time and they have to proceed without them. So while there’s a demand for impact evaluations, maybe they don’t have the time to wait for these results or there are many other political considerations, that we as evaluators are only slowly becoming aware of, which tells us that we need to scale our programs up and we have to learn to be adaptable and to navigate our way around these constraints and make our evaluations more useful to policymakers. We also try to explain to policymakers that a well-done evaluation can inform them more in the long-run than something quick and small. However, this is a principle- agent kind of a problem and they have different motivations and tasks from evaluators. We have to find a way to work together.

RB: Impact evaluation for policies, done by a country on a large scale, seems to be a method that requires a lot of resources and manpower and there’s a also a time constraint involved in the evaluation process. Is there an alternative to this option for countries that do not have the required means?

BB: The quickest and perhaps the best use of resources is to build an impact evaluation monitoring system that tracks outcomes. The government, even though is investing in a lot of MIS (management information system) and already has a few good systems in place in some schemes, we find that they only stop at inputs. Perhaps having outcome level data would be really great. Secondly, along with robust MIS systems, we need good qualitative work that gives us better insight into a field. Thirdly, we need a synthesis system which basically compiles findings from different small studies and is able to better inform impact evaluators. These are just methods which are one-time investments and won’t have too many costs involved after setting up. All methods concentrate on getting the correct information out to the public.

AA: The decision regarding an impact evaluation project will involve a cost benefit analysis wherein the cost can reasonably be estimated, yet the benefits- evaluation of a program- is not easy to measure, how then are decisions taken about which evaluation should be done and which not?

BB: It’s not so much about the evaluation to be considered but about which programme should be undertaken. The costs are of the evaluation but the benefits are of the program. These benefits can actually be captured only if we find out whether it was taken up by policymakers, did it create change or inform any of the stakeholders in a better manner etc. It’s very hard to attribute a money value to these things. In this case, we look for other methods that try to calculate the benefits of the program.

RB: What are some fields in india, where you feel impact evaluation should play an essential role?

BB: Flagship programs and innovative programs that are likely to be scaled up in the future are the basic areas that definitely require impact evaluations. Innovative programs are piloted and have potential and these need evaluations to inform and assess the possibility of scaling them up. Not only impact evaluation, but they also require what’s known as process evaluation. These assess the benefits of a program going from a pilot stage to a principal stage. Impact evaluations, in themselves tell us whether a program works or not. To understand why and how it works involves process evaluations, which are embedded in impact evaluations.

AA: On a lighter note, we are curious to know, what motivated you to enter the field of impact evaluation?

BB: I’ve always wanted to work in the development sector. This is a niche field that is methodologically rigorous but at the same time, you don’t lose sight of the real problems. It allows me to do my own research, making use of my training in this field and also keeps me grounded in the realities of what’s going on.

You can access the presentation used by Dr. Barooah here: Teaching impact evaluations